Fall 2020 // ReLab Week 11 Class Discussion

Mariana Sanson:

I have to admit that I struggle a lot with understanding how software and hardware work. I’m highly visual and the process in which software and hardware work are extremely complicated to me, so much that I rather choose to ignore it and use what is easier. Shamefully, I have to also reveal that last Summer I had to use a computer at a UPS to print a label, the software was Microsoft and I have not used it in more than 10 years. I did not know how to eject my hard disk and I panicked and instead of requesting help (because a. I felt silly and b. I did not want to distract the employees with my lack of ability), I turned the computer off. On my way home I kept thinking about how the software used by Apple has become so attached to me and the way I also relate with other technological devices that I do not know how to use other software (and even hardware). I think that I have understood computers without permeability at all and all of my interactions with computers had never actually had a “genuine interaction” but after the readings this week I can understand better why it is important to “understand how they’re determining access to information, knowledge, and creativity”.

Lori Emerson’s “Interface” text helped me understand, and also to find that it might be common the reason why I choose to ignore the process and how the software works. I’m a designer, therefore I use software to design, I do not ask myself how it works, I just design with it. Though during my BA I did have to learn how to design without software, how to trace lines, use grids, use art tools in order to design without software. These days I’ve been seeing a lot of videos of people in TikTok explaining how to design or use some elements of designing with Microsoft Word or Powerpoint, at first I thought this is so silly, why would you do that on that software when Adobe makes it so much easier with any of their software, but then I realized that Adobe is really expensive and not everyone has access to it or it’s taught how to use it (most of my BA studies I had a cracked version of Adobe suite). Since then I’m very intrigued and fascinated by all of those videos where mostly teenagers explain how to design with Microsoft (something I would have never think about doing it myself before).

I tried to remember my first interactions with a computer. I remember my father’s computer in 1994 and how the screen (black and green) was something puzzling and not at all understandable. The only thing that I did understand about computers in 1994 was that my Dad would print me Disney illustrations for me to color. I can see the connection about how I relate to software and hardware in my adulthood.

Emerson’s explanation about the impression users have of interactions with computers (and no computers) via an open-ended dialogue, reminded me of a night I was babysitting one of my little cousins, he was 4 years old. He was playing with his iPad (his other nanny) and I heard him starting a conversation with Siri:

Siri, where’s my mommy?

I don’t know who’s your mommy

Well, my mommy is a very important person in my family…

And he continued explaining. Of course, I intervened and explained to him but my point is that new generations relate completely differently with technology and they understand reality as completely mediated by technology. Do they know reality without that mediation?

Emerson also stated, “…unseated as technical reproducibility creates the possibility for every viewer to be an expert or even, in contemporary terms, a ‘maker’.” I think a lot about this, I tend to see it from the positive side, I think about how it “democratizes” the means of production and allows more possibilities for creators. But I do understand that this powerful tool also implies someone can do a lot of damage by spreading lies or fake stories. I am mesmerized by the power of TikTok, though I’m a victim of a “planned obsolescence” in my own phone, it has no more space to add another app and I cannot use it.

In Jennifer Gabrys text I found a lot of connections and answers to a project I created for my Transmedia course last semester, Women Memory Archive. It is long but it aims to reconstruct Women’s representation in Mexico since patriarchy has constructed us as murderable. While doing it, I also planned it to gather information, more specifically data to work as “digital humanities”. I wanted to gather information about how women feel, how many times a day they feel in danger, what things make them feel represented, and with what they find identification. I would be working with simple concepts, like colors, because Mexico is still extremely patriarchal and genderized. My idea was to make visible through Leds building installations the multiple forms in which women can feel represented. Also, to use the numbers about how many times a woman feels in danger through LEDs installation, every time a woman feels in danger, a light turns on. All of this information would be collected through an app and I would also provide opportunities to engage without the app because not everyone has access to wifi or a cellphone. The project is more extensive and it also involves a website, physical video archives, creating content, museum exhibition, traveling booths, etc.

Notes:

- I looked online for the book Further Reading: Oxford Twenty-first Century Approaches to Literature and it is so expensive. I miss the Library so much!

- This summer my Wacom tablet became a Zombie Media device ): it no longer works in the current macOS software, but it is perfectly functional and works on any other devices or older software. If someone wants it, I would be happy to gift it or I would happily donate it to the lab!

Khokhoi:

“Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method” acknowledges historiographic orientation of circuit bending to reawaken & resurrect media considered dead by standards of consumer userability. Harvested from fine geological matters, these media objects will continue to inhabit our geologies long past our lifetimes. Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parrikka’s main point in their paper is to situate circuit bending within archival practices and artistic methodologies.

This is an example of an artwork (from my current location and home island of Bantayan, Philippines! shown at “Equations of State” Silverlens Gallery in Hong Kong (Links to an external site.)) made through circuit bending a broken karaoke machine into a mechanized system that replicates the mangroves exposure to water in accordance to the tides. This piece emerged in collaboration between artist Martha Atienza and a local karaoke machine maker, through a process of thinking through the visualization of climate change impact on local ecosystems.

In the emphasis on “amateur” “hobbyist” & “DIY” practices for circuit bending, one should also emphasize community collaboration, networks, as an analytical and creative method of art making. Many media devices in recent decades are made for personal private consumption, and rewiring that media means also altering the framework of the hyper individualist consumer in favor for community-based hacktivist practices. Thinking back to previous readings, I would say this comment is coming from a “feminist media archaeology” perspective that looks not only at the materiality of media, but also acknowledges & understands the intimate relations in which media is used that can inform media archaeology.

In the examples of “Citizen Sensing,” readymade sensor kits were used for community-based “monitoring, reporting, managing” to establish environmental engagement. As Gabrys notes, this process must go beyond “celebratory formula of gathering data for political action and change to open into particular worlds of inquiry and political contestation [where] new relations and communities might be put into play and activated.” Within this process also emerges a politics at the intersection of “sensor technologies, citizen participation and environmental change” where media tools become used for collective action. Still, Gabrys suggests that the practice-based research of citizen sensing is open-ended cultural and political engagement. I’m curious if there are successful models of citizen sensing that manage to make it to legal cases & environmental change?

Another example of what might be called ‘citizen sensing’ but employs embodied tools is in Natasha Myers work “Becoming Sensor.” (Links to an external site.) As a practice to decolonize ecological sensorium and relations, she invited community members of Toronto’s Oak forest to experiment with “sensory practices that document the growth, decay, combustion and decomposition” of this environment. Myers writes: “Our protocols reinvent ecological modes of attention and data forms by cultivating synaesthetic attunements to the land through forms of kinesthetic imaging and kinesthetic listening.” That this projects works with indigenous peoples on settler-colonial territory shows how practices of ‘citizen sensing’ can be instrumentalized for forming new communities, polities and politics.

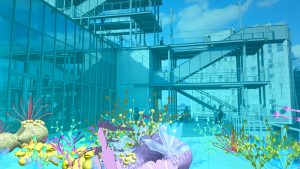

Lastly, in “Interfaced,” Lori Emerson dives into this notion of mediating space of technological boundaries. What we take for granted as a media environment – whether that be Apple products or Microsoft word – is actually a built interface that becomes inhabited by consumer habits. Going into discussions of hardware, software and literary interfaces, Emerson then asks, “how do we read interfaces that may not yet be invisible but that are being pushed far outside our line of vision and touch?” Thinking back to last week’s readings, I understand this as also a question of decolonization of borders and boundaries that define our interface with space-time. Emerson ends the discussion by speaking to the possibilities of VR to bridge virtual and real interfaces. Given some of the disadvantages with VR mentioned, I also think of the potential of AR to point to porous interfaces of digital reel and emerging bioecologies. I am reminded of the works of Tamiko Thiel, like Gardens of the Anthropocene (Links to an external site.) and Unexpected Growth (Links to an external site.), that imagine the proliferation of these interfaces.

Rachel Pincus:

I have always been drawn to the art of circuit-bending, circuit-bent toys in particular, and reading Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka’s essay on “Zombie Media” led me to examine why this is the case. I think from a young age, I had certain animistic beliefs about technology. In particular, I developed a fear of talking, electronic toys because of the way they would glitch and make strange noises when their batteries were getting depleted.

In particular, there was a toy parrot called “Pete the Parrot” that I had as a child that would move its wings and repeat what you said back to you (albeit in an already distorted, poorly recorded form). I encountered a malfunctioning Pete the Parrot at a friend’s house and for months afterwards would flee from the room whenever I saw one.

The gradual way this developed is evocative of other “haunted” aspects of media from my youth such as VHS tape generation loss, and also made it hard to anticipate when you would activate a talking toy one day, only to hear slowed-down, demonic noises.

Actually, I think my reaction to these toys may not have been so animistic as I thought; maybe it was the rupturing of animism, immersion and black-boxing that caused my young psyche so much distress. You were supposed to believe Pete the Parrot was alive, but this went to pieces when you could literally hear his interior circuits misfiring. In these newer videos, you can hear the children, perhaps more media-savvy than I was at that age, finding the humor in the voice that an adult might.

I am drawing this inference from one related phenomenon I experienced as a child, that that has been studied academically because it was such a shared cultural experience in the late 90’s: the Missingno (Links to an external site.). character in Pokémon games. This glitch placeholder character, whose name (entered by a developer concerned that people would find it – “Ketsuban” in the original Japanese) stood for “missing number.” According to an analysis by professor of education Julian Sefton-Green, observing his son’s reaction to the glitch, it was the first time for many children that the illusion of the “enclosed” game had been broken. Other children came up with lore to re-integrate the character back into the game’s story and world.

At age 8, I personally ran screaming from the room when my best friend Matt first showed the glitch to me, but the character and the aesthetic around it continued to hold an almost erotic pull and revulsion for me, and today I definitely seek out this sort of frisson in my personal explorations of media archaeology (that’s how I have so much YouTube videos and other material).

Daniel Pemberton:

The question of interfaces, and the black boxing of the devices which make up our everyday lives, contributes to the many confusions present in conversations about media, and technology more broadly, had in the public sphere. A primary confusion being the problem of precise definitions – what do we mean when we talk about the effects of algorithms or surveillance, or interfaces for that matter? Media technology finds itself stuck in a middle space of being both “banalized,” or something we are estranged from and thus view as harmless, or “mystified”, as in the moments when that estrangement becomes an ominous yet vague sense of distrust (i.e. when things stop working, or when the algorithm uncannily works too well). The friendship we have with our devices is an uneasy one.

A recent conversation I witnessed on Twitter: “I don’t know what an algorithm is and at this point I’m too embarrassed to ask” – Response: “Literally no one does, u good”.

The media scholar today has their work cut out for them in not only clarifying these discussions, but also finding some stable ground upon which to think about and theorize technology. The two conditions mentioned above are both symptoms of the black boxing and the hermeneutic closure the practice creates. This is not only a practice in the design of technical objects but is carried out at all levels in tech firms and media companies, we encounter proprietary black boxes all the way down.

Opening the black box is not just a technological problem but one with wider political and economic implications – as noted by Jennifer Gabrys in her study of “citizen sensing” technology and practices. When users begin to gather their own data, on pollution for instance, immediately there arise complications in the accuracy of data and the ability of the communities to speak their concerns to the oil and gas companies which cause the pollution in the first place. Similarly, opening the black box is not as simple as taking a crowbar to your imac air or throwing a rock through the window of an Apple Store – as necessary as both of these may be.

Further complications arise when we consider the ecological impact of use and reuse. Those in the reuse camp are attempting to push back against the waste producing epidemic of planned obsolescence, an act which can quickly find a tinkerer in deep legal trouble such as in the case of Rich who refurbishes Tesla cars. This involves not just a salvaging of the physical components (hardware), but digital ones as well (software), as the Tesla machine operates through a proprietary OS. In the internet of things it is not just computers which become black boxes.

To bring the discussion back to interfaces, it is Lorie Emerson who connects the concepts of the blackbox and the interface by calling upon an understanding of the term interface which emphasizes its mediating function as being semi-permeable and through which (paraphrasing McLuhan) “humans and media engage in a never-ending process of translation and assimilation into the other’s terms” (Emerson, 5). Contrasting this to the world of HCI in which the circuit between media and human become one-directional, the interface as such begins to seemingly disappear as our machines become more closed off to us. This is especially true as HCI becomes less about discreet moments of interaction, and more about continuous and dispersed interactions between a networked host of objects as with the internet of things. The interface as such “disappears”. However it is not gone, only invisible, making its power to delineate our interaction with the world harder to detect. Not only are we unable to change what happens “on the computer side of the interface,” but the citizen turned user is now excluded from influencing what happens behind the black box of corporate power and the ascendency of Silicon Valley oligarchy. Power as such does not disappear, it only finds more covert means of delineation.

Rich the Tesla jailbreakers:

Note: Gabry’s story of the northwestern Pennsylvania community which armed itself with pollution measuring technology was of interest to me. I grew up surrounded by the carcinogenic oil refineries of Southeast Texas along the Gulf Coast. This means I not only spent my younger years inhaling massive levels of toxic byproduct in the air but was also inundated by ExxonMobil propaganda, their grip on power in the community is strong. I am interested in taking some of this technology for a spin, granted I can get my hands on some, next time I visit. Perhaps the area could use a similar squad of “citizen sensors”.

Claire Haughey:

Maris Hutchinson:

‘The role of the creator in the twenty-first century may very well be one of perpetually revealing what is concealed by both medium and interface’

I found this sentence at the end of Lori Emersons’ essay, and it’s entirety, to be positing a perspective that shifts my understanding of both a ‘creator’ and a ‘user’ away from the active function of a technology to that sliver of interface interaction that is described in the essay where mutual permeability with the user *should* be. The function of the interface has become, through this reading, a two-way mirror, although unbeknownst to the user, who is only looking into a one-way mirror with a hard backing, impossible to get past or comprehend, whilst believing only the intended purpose is being served. The comprehension, or lack thereof of this false transaction is what I find curious as a user of technology. It seems as if in part blackboxes represent things that people partially don’t want to think about and technologies have leaned into, taking awareness/tasks from users, with their complacency.

I think of how I use technologies daily. My main devices, phone, computer, are primarily used to perform task functions (captures/processing images/phone calls/emails/texting) and to hold onto things and organize materials in places that I *think* I can access. Yet, they mostly function as a place that I put things and never interact with again. I feel as if I can trust the computer/phone to have processed and dealt with/diseminated whatever information and stored it, while I haven’t actively had to make a decision about sorting/saving it. Or when I’ve sent an email or a text message that perhaps I wish I could redact, I can delete it from a device, and while knowing its still in the world/accessible if needed, I can feel the act of deletion has resolved the situation.

The line where advertising campaigns and research show that users will bend at to exchange information, autonomy and money for the convenience of the technology, seems to be the place to start scratching the surface to see inside. There is something overwhelming, intendedly so, about the whole black box. The example in this article illustrates how the advertising tells you where they want the product to land in your lifestyle, and is an important insight as to where the new horizon of interface would like to be, from the technology makers standpoint . The reliance then created by the looping of technologies together, with updates and compatibility, ports and obsolescence function by pushing this line collectively into further dependency on the apparatus of the technology. Beyond an individual technologies interface, I wonder where the larger systems ‘interface’ exists– and if these are brand specific in how users get looped in. Does the apparatus of interface exist more within our individual lifestyle choices, such as using a phone as an alarm clock or a watch, then in the actual device itself? Where for an individual do we start to see the one-way-ness of each interface?

Livia Foldes:

As Emerson traces the shifting meaning of the term ‘interface’ from its former associations with permeability to its current denotation of impermeability, I was especially intrigued by Emerson locating its origins in the human body:

In this usage, one’s face or visage is seen as a kind of permeable boundary lying between one’s inner life and the outside world—a usage that also brings to light the fact that western culture has been struggling since Plato to overcome technology-related boundaries such as writing in order to have a more direct relationship between oneself and the outside world.

Emerson’s analysis of contemporary interfaces focuses on what we see—or don’t see—on screens, while Hertz and Parikka focus on hardware obscured by black boxes. Gabrys locates interfaces in environmental sensors and tracking platforms, and, perhaps, extends the definition of the interface to “a set of practices” that are “bound up with environments, communities, institutions, and wider politics.”

I’d like to pick up Emerson’s bodily thread to think more about interfaces in and around our bodies, mediating between body, machine, community, and physical world. In an essay by Kelly Pendergrast (Links to an external site.) that I love, she contrasts the visceral bodily metaphors (“meatspace,” “jacking in,” “the new flesh”) of ’80s and ’90s-era cyberpunk—and the wired machines they were in dialogue with—against our current wifi and Bluetooth-connected technologies: “blobs of untethered plastic and aluminum that are sleek but sexless, with hidden seams and untouchable insides.” What do these seams hide? For Emerson, sleek interfaces “foreclose on our access to information, knowledge, and creativity”; for Hertz and Parikka, black boxes force us into a ceaseless cycle of engineered obsolescence and consumption. Pendergrast focuses on elisions of labor and material extraction—”that space behind the curtain is Marx’s hidden abode of production, where workers toil and delicate consumers fear to tread”—and ultimately surveillance.

But what happens when the seams are inside us? A very recently published HCI paper (Links to an external site.) introduces the new acronym HInt, for Human-Computer Integration, “an emerging paradigm in which computational and human systems are closely interwoven” and “user and technology together form a closely coupled system within a wider physical, digital, and social context.” The paper traces successive eras of human-computer interaction from mainframe (many:1), through PC (1:1), mobile (1:many), ubiquitous (many:many), and finally to integration, which is distinguished by a truly blurred boundary. It goes on to discuss many individual and social repercussions of this blurring, and introduces some fascinating frameworks for how we can define different kinds of human-computer integration—for example, by scale, from an individual organ, to a single person, to a society; or by where agency lies, whether in the human, the machine, or somewhere in the middle.

Predictably, the paper fails to acknowledge any potential repercussions for labor, material, and environment; if we consider it a guide to the near future, it appears that our current elisions will continue unchecked. As our interfaces recede further from view, perhaps even facilitating a simulation of an unmediated relationship, how will we design and demand forms of integration that don’t foreclose on the possibility of accountability and equity?

Sarah Wolfe:

According to the EPA, e-waste accounts for 2 percent of the trash in US landfills, but 70 percent of the total amount of toxic waste. Hertz and Parikka add extra data in this week’s reading, saying that the country discards about “400 million units of consumer electronics” and that “two-thirds of all discarded consumer electronics still work.” Missing from this is the obvious fact that a chunk of e-waste from the US is shipped off for sorting and recycling in developing nations, such as China, Ghana and Pakistan, where it’s cheaper and where the lack of proper safety regulations endanger the local populations and environments.

In considering the life of consumer products in general, I think of the many events I’ve attended as a member of a vintage/swing dance society. We celebrate the 1910s-1940s through authentic costuming and engagement with items manufactured before the 1950s. You can see first-hand how these older products were built to last — and have lasted. It’s no secret that modern-day consumer items, particularly technology, are designed to wear out, break, and to have shiny, new upgrades so that we’ll keep buying more (which supports the destructive disposal cycles mentioned above ). I knew that quality began to decline in the 1950s, which I thought was primarily from the mass manufacturing/cheaper materials approach that came from WWII factories and that was used to encourage a regrowth of post-war economies. Hertz and Parikka’s article, however, paints a fuller picture for me about the history behind this “planned obsolescence.”

The basic idea was first tackled by Alfred P. Sloan Jr. of General Motors back in the 1920s, but it was Bernard London in the 1930s who coined the actual term and presented a fuller outline. London saw planned obsolescence as a solution to the Great Depression, a time during which people were holding onto or repurposing their items and, as he believed, ‘prolonging the economic downturn.’ His proposals for adding expiration dates and taxing citizens who continued to use the products obviously didn’t fly. It wasn’t until after World War II that manufacturers of clothes, tech, cars, etc. began to artificially decrease the life span of products through planned obsolescence as well as the creation of a “special urgency” through advertising that tried to coerce consumers into believing they needed – and deserved – the ‘next new thing.’ Hertz and Parikka point out that planned obsolescence “takes place on a micro-political level of design.” Parts are deliberately hard to replace, items are only manufactured for a short time, and plastic enclosures break if opened – which you could say is somewhat akin to a ‘black-boxed system.’

Knowing how intentional and ingrained planned obsolescence is in modern times, it’s hard to imagine we’ll ever break the cycle of unethically harvesting the earth’s materials from Global South countries to create products for ‘short-term use’ that we then toss out and that end up being shipped to these same countries. Though I greatly value the idea of circuit bending and using media archaeology to inform artistic practice, it’s a solution that solves a small piece of an overwhelming global issue. Not counting a sudden and devastating planetary disaster (versus the ongoing environmental one playing out each day), it would take a monumental shift to stop the speeding train we’re all on. There’s the continual hope to eventually create a closed recycling system where all materials within e-waste are recovered and reused to create new items while producing zero byproducts. Rippling out from that could be what Hertz and Parikka call “depunctualization.” Though they relate it to dismantling tech, it could also be applied to upending the current manufacturing system grown from colonialism; to eradicate the destructive harvesting of resources and e-waste dumping and to then rebuild a more equitable framework where fair and balanced community/global relationships can begin. Perhaps this re-imagining is unrealistic, but one can still hope.

In regards to the Gabrys piece, I found the concept of citizen sensing interesting – particularly how it can be considered a technique that requires ongoing practice to develop (as mentioned by Canguilhem) and that has the opportunity to become an ever-changing area of study that incorporates many fields, including politics, environmentalism and community activism. I do agree, however, with the issue Claire brought up about placing the responsibility on communities for data gathering, particularly the lower-income areas that are often the most effected by pollution. Questions arise about why it should be their responsibility to do the work instead of agencies. Additionally, questions of fair compensation come up if people do participate, similar to Livio and Emerson’s discussion of the construction of the ethical, feminist lab.

Eden Turner:

What struck me most while watching Apple’s Ipad Pro “What is a Computer?” ad was the comparisons between the dynamic characteristics of the child and the dynamic functions of the device. This “child of the future” leaves her Brooklyn apartment on her bike, jumping from place to place, engaging in conversation with friends, Facetiming and texting with other friends, using her iPad to write a paper on the street, biking through the park, taking photos, drawing on her iPad, texting while ordering tacos, browsing online while sitting in a tree, reading comics while riding the bus… While this video is obviously showing the versatility of the functions of the iPad, it is also commenting on the younger generation’s unique ability to multitask in every area of their life. Emerson writes, “The iPad overcomes all boundaries that might keep you estranged from any place, person, thing, or experience.”

As we’ve learned in this course, there seems to be a widespread assumption that new technology advances us into the future, helping us do more, think more, see more etc. There is an idea, portrayed in this video, that technology actually brings us closer to our surroundings and the people in our lives. But much of what we also learn in Media Studies is to question this very assumption by observing the effects technology has on ourselves and the world around us. While this ad was clearly designed to sell a product, it could also be argued that it was attempting to sell a certain kind of person/lifestyle. This modern day “renaissance” person can multitask online and off, while technology allows them to access the world beyond just their immediate surroundings. The person and machine work in tandem to create a world with limitless possibilities, while the person in the ad is effectively living life through the iPad.

But is this a true representation of the lifestyle technology gives us? Emerson writes about disappearing interfaces being a purposeful design strategy, “digital devices whose interfaces have been intentionally designed to disappear from our awareness; without an ability to see where one thing or person or experience ends and another begins, we are left in a state of constant estrangement.” These devices extend beyond their limited physical form to create a portal of sorts for the user and it’s designed in such a way that the machine itself dissolves while in use. But the machine never goes away, and no matter how intuitive an interface is, it is not organically connecting the user to their surroundings.

Morrison Gong:

In Jennifer Gabrys’ Environmental Sensing and “Media” as Practice in the Making, she discusses the project of citizen sensing. It aims at collecting different data and information from its users and apply them to science, geographical, urban and environmental studies. It has also contributed to media communications in areas such as art, design and architecture. Emerging technologies provides us with many ways to monitor and locate digital media. The projects have been divided into three major categories: “pollution sensing”, “urban sensing” and “wild sensing”. In northeastern PA, the sensing project developed to be an interactive one in which the researchers can communicate with the users/residents and come out with the optimal way of tracking. “New relations and communities might be put into play and activated through monitoring practices, or existing communities might re-encounter old problems with the difficulties of finding ways to hold environmental regulators and industry to account.” (505) Citizen sensing has created its own politics and has generated problems about the legitimacy of its data; as Gilbert Simondon says, technologies articulate cultural values, and there articulations might also serves as sites of cultural experimentations. (509)

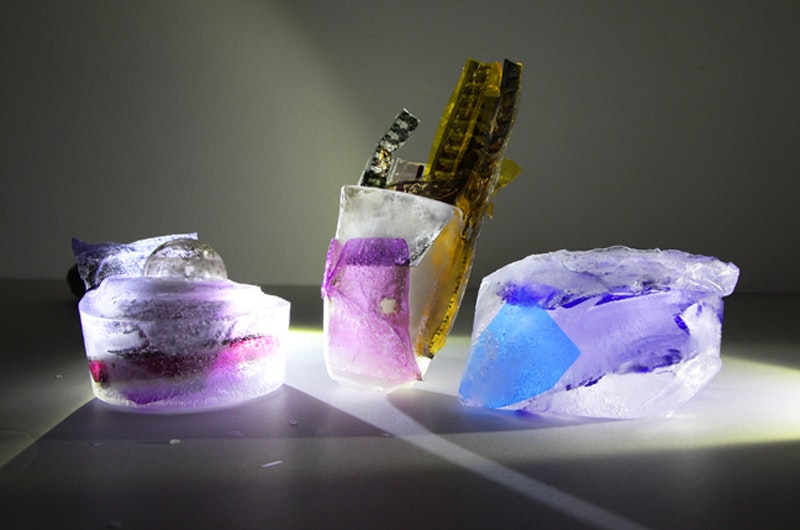

Hertz and Parikka’s Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology Into An Method, they argue that the speed that media becomes obsolete is rapid. The temporality and memories media embodies is “not only human memories, but also the memory of things, of objects, of chemicals and of circuits.” I like the connection the authors are drawing between planned obsolescence and repurposing consumer products into artistic practices. Since Picasso and Duchamp, a lot of artists have been using electronic products as ready made and collage (Nam June Paik) Media archaeologists are circuit benders that transgress the rules of planned obsoleteness of technologies. The digital realm provides immense space and potential for the avant garde. This reminds me of Bradley Eros’s works made of ice at his exhibition at Microscope Gallery in 2017 (All that is solid melts into eros (Links to an external site.)) He puts film, electronic devices and color gels in water and freeze them in ice, which suggests not only the futility of art economy and preservation, but also the ephemerality of technology, or beings in general. Bradley Eros states regarding his exhibition: “Choosing liveness over permanence, I point to a philosophy of the living process, the present moment, non-possession, non-attachment and energy exchange”. Re-using and re-purposing media devices can provide us with new perspectives of how culture, ecology and technology relate to each other and develop new relations.

asasas