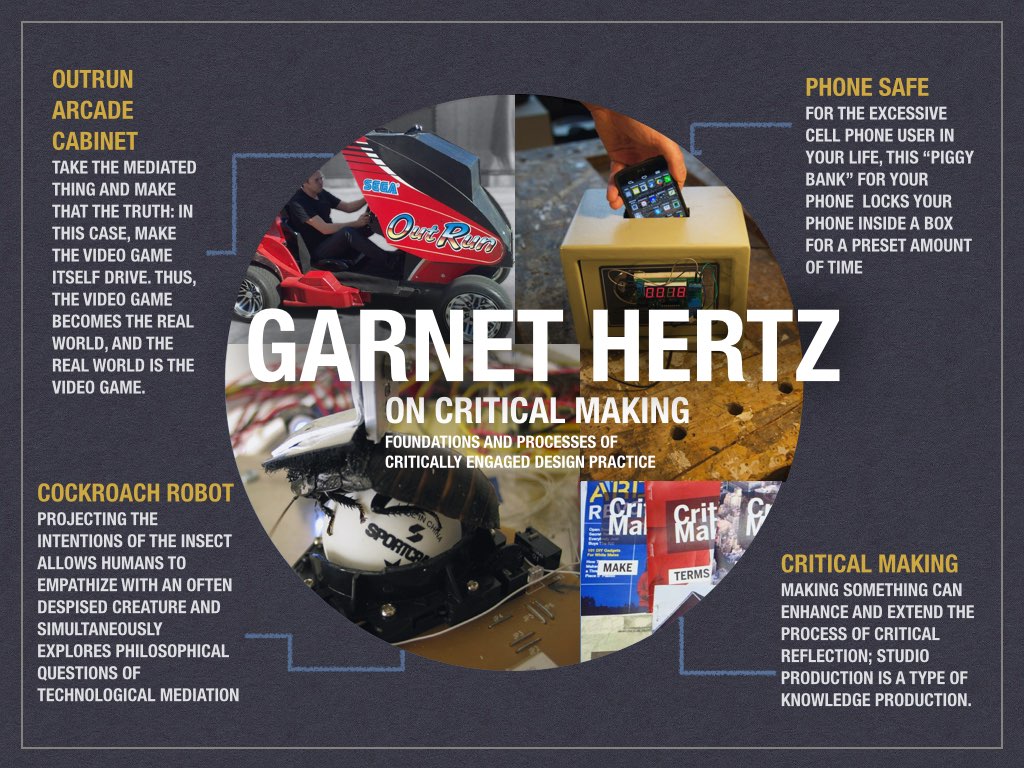

Garnet Hertz on Critical Making:

Foundations and Processes of Critically Engaged Design Practice

Nitesh Singh, Mariana Corona, Joanna Aliano Ruiz

“No cockroaches were hurt during the making of this project,” Garnet Hertz reassured the audience after introducing his exhibition project Cockroach Controlled Mobile Robot. “Well, the only time I’ve actually had them die was when I fed them lettuce that was leftover from a hamburger…and it’s because it’s filled with pesticides. I didn’t think about that,” Hertz, Canada Research Chair in Design and Media Arts and Associate Professor in the Faculty of Design and Dynamic Media at Emily Carr University, quipped. “But that’s another lecture.”

Ben Vershbow and Dragan Espenschied: Archives, Artifacts and Digital Culture

Group Members: Michelle Wainwright, Melinda Jeune, Annette Slaughter and Ethan Arnowitz

“The future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed” – William Gibson

New York City has inhabited the island of Manhattan for nearly 400 years. The New School University Center just celebrated its first birthday. Have you ever stopped to think about what used to exist where The New School stands now? What about your East Village apartment, or even the Deli around the corner?

While it can be easy to get caught up in the fast-paced, subway-commuter lifestyle of Manhattan, it is important to appreciate New York as a city built upon many layers of history, and to realize that these historic details of our city’s past are crucial in developing its future.

It is this “layer cake of history” that Ben Vershbow, the director of New York Public Library Labs, and his team devote themselves to — and to discovering and reformatting that history in a way that is interactive, user-friendly and inspiring. NYPL Labs is reinventing the way we think of the public library and, through a variety of exciting projects, creating a framework others can use to build our community.

One area NYPL Labs is particularly fascinated by is their map collection and the development of digitally interactive tools to turn old maps of New York City into relevant information the public can use today.

For instance, contributors have used the “Map Warper” — developed in 2009 and getting a makeover later this year — not only to align myriad maps, but also to trace the outline of 150,000 building footprints on those historic maps. Those plotted buildings then become searchable entities. However, because this process is not fully automated and often requires a user to quality-check the data, it has proven to be a time-consuming “bottleneck” process. Thus, NYPL Labs has integrated creative crowd sourcing to aid in the work. “Building Inspector,” a related crowd-sourced mapping tool, aims to tap into the casual, spare time people spend on a daily basis surfing the web. It seems to have worked, as over one million classifications have already been produced.

Ben and his team are especially excited about a new project NYPL Labs has in the works titled “NYC Space/Time Directory.” After winning a grant from the Knight Foundation, Ben and his team are planning to build a service that uses historical data of old New York in a way that is relevant to the New York we know today — a kind of “Google Maps interface through time.”

Through this community-driven directory, one will be able to look up historical locations, events, and people in context and “eventually enable augmented reality-type experiences.” By reaching out to historians, other institutions and the tech community, NYPL Labs hopes to build a framework others can work off of, essentially allowing historical information from maps, letters, pictures and more to be searched the way we search things today.

The innovative projects underway in the NYPL Labs are part of a growing movement to bring our culture and history into the digital age. This movement has proven to be a great challenge — finding a way to present archived information in a way that is meaningful and accessible using technology. This is part of a larger enterprise known as “digital conservation,” which seeks to ensure that historical materials are digitized and conserved, and that born-digital materials will be retrievable in the future.

Dragan Espenschied, a self-proclaimed Digital Conservator and Media Artist, shares Ben’s sentiment that the internet can be used as a tool for preserving endangered information. As the internet has become integrated more and more into our daily lives, it has begun to drastically change the way we interpret information.

In 2011, Dragan helped develop a project called “Once Upon,” which displays the exponential evolution of internet browsers with each passing year. Internet browsers are perpetually being updated (ostensibly) to help us better filter and visually process the information we seek online. To further illustrate this evolution, he presented a tutorial of what it would be like to browse the internet in the present day using a Netscape browser from the 1990’s on an antiquated computer desktop. The browsing experience was less than ideal compared to what we expect from our current browsers; it was riddled with glitches and errors, and it loaded at a fraction of the speed we are used to today.

Another one of Dragan’s projects, one that truly blends his two titles of Digital Conservator and Media Artist, was his Facebook spin-off. The spoof of the heavily used social media site demonstrated how users would have interacted on Facebook if it were established decades earlier. The Facebook spin-off is an enlightening example of how current trends, events and technological capabilities affect the way we interact and the language we use on social media.

Today on Facebook, we establish the value of other users content by clicking a “Like” button. However, Dragan maintains that had the website been established before the boom of the digital age, we might likely use the term “Vote” to show our appreciation for a status or picture, as that was common language regarding internet participation. His project also demonstrated how different the format of a social media website would be, due to the drastic difference in internet browsers of the time.

The true beauty of the internet is that the amount of information that can be accessed by a single user is unimaginably expansive, especially due to the fact that anyone with an internet connection can potentially contribute their own information. Dragan demonstrated this potential using the idea of “Digital Obscurity,” which is the act of a user encountering content on the internet that has previously gone entirely undiscovered.

Dragan shared an example of Digital Obscurity by displaying a homemade computer game discovered by a friend on an archaic hard disk drive from the early 1990’s. This primitive game, titled “Bomb Iraq,” was little more than a digital flipbook, but nonetheless it was likely that it had previously only been seen by the original creator. This deeply intimate discovery is a prime example of how the internet can create connections that would have been impossible decades ago.

It is clear that the internet has been used largely to help connect us with the world outside of our communities, but it also helps us connect more deeply with the ones we live in. Through Ben’s projects in the NYPL Labs, he proves that physical archives can provide great meaning and serve as a force for cultural enlightenment when merged with digital tools on the internet. These projects, linking the past and the future, demonstrate one possible vision of our libraries’ place in an ever-evolving digital culture — one that is still situated within an ever-expanding digital and analog past.

Furthermore, digital conservation and the projects Dragan has undertaken are increasingly important as we take the internet into a new age of utilization. To study its development and ever-changing nature will be crucial in order to optimize the way we integrate the internet and other digital tools into our daily lives in our search for information — not to mention preserving the internet itself, as one of the key cultural productions of our time.

Notes on/response to Brian Larkin’s presentation:

“Techniques of Inattention: Religion and the Mediality of Loudspeakers in Nigeria” March 9, 2015 @ The New School, NYC

| “Secular Machines” | Why Loudspeakers? | Sonic vs. Visual Media |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Loudspeaker on Bicycle (Northern Nigeria) – Source: Brian Larkin “Techniques of Inattention: Religion and the Mediality of Loudspeakers in Nigeria”

|

NYC Street – Source: “USA-NYC-Koreatown99” by Ingfbruno

|

|

Acoustic Violence and Inattention

- The aggressive religious soundscape in Nigeria facilitates religious division among residents

- Nigerians must practice inattentiveness and dismiss religious media they do not affiliate with

- At what point does sound become violence?

Media and Inattention—A Problematic Relationship

In media-rich urban cultures, where the visual and sonic assault can be at times overwhelming, we urban dwellers often have to cultivate techniques of inattention. We have to learn how to filter media and their messages—particularly those that seem to be aimed at different target audiences. But to what end?

Media and consumer inattention evolve in parallel. They form a positive feedback loop. As consumers become better at filtering media, media become more difficult to filter – more aggressive. The volume knob on the loudspeaker gets turned up, so to speak. And at a certain point, it can become violent. The aggressive religious soundscape that exists in Nigeria, for instance, facilitates a sense of religious division (intolerance even) among residents. The loudspeaker, then, can be seen as a sonic weapon—a form of acoustic violence—that plays a role in aiding the conflict between religious organizations in Nigeria. Media that forces itself upon consumers in this way can be seen as an weapon of violence that should be confronted.

Inattention has a breaking point. If we step back and look at media from a purely marketing standpoint, its basic purpose is to encourage consumers to support a message. It could be argued that imposition plays no role in this. As soon as a consumer is forced to attend to a message, despite her conscious efforts of inattentiveness, the experience becomes negative. However, as the loudspeakers in Nigeria show us, imposition is sometimes a fundamental purpose of media. As Larkin points out, the loudspeakers in Nigeria do not enhance the messages being relayed. In fact, the loudspeakers often distort the sound signals and are largely just a way to impose sonic control over a particular space. In such instances, media can be seen as an assault against the free will of residents. As technological media continue to evolve in response to consumer inattention, we need to cultivate better awareness and governance to appropriately balance the rights of media makers and the free will of consumers.

JOE INZERILLO: “MATHEMATICAL INTERPLAY OF ACCELERATED BODIES; OR, HOW I LEARNED NOT TO SLIDE INTO FIRST BASE”

Ashley George Maritere Berrios Pizarro Kaylie Schneider

On March 16, 2014, Joe Inzerillo, Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer at MLB Advanced Media (MLBAM), gave a fascinating lecture, as part of the School of Media Studies’ lecture series, on technology and baseball, as well as his organization’s developments in live streaming and Internet technology.

Source: pmcdeadline

Baseball has a long history of integrating innovative technologies both on and off the field. Thomas Edison chronicled one of the first games at the onset of film in 1898. Even the field environment itself, seemingly the most “analog” of environments, has improved with the advancement of architecture and technology. A few notable examples include Philadelphia’s steel and concrete Shibe Park construction in 1909, the first three-tier structure development at Yankee Park in 1923, Fenway Park’s introduction of lights in 1933 (with night baseball launching at Crosley Park a few years later in 1935), and the Astrodome equipped with air conditioning in New Orleans in 1965. And over the years the live action on that field has been “augmented” with scoreboards, statistical displays and screens for instant replays. Film, photography and motion graphics have transformed the way we mediate baseball for remote viewing. MLBAM represents the next step in our technological “augmentation” of baseball, and is now engaging in a high level transformation of how baseball’s fanbase interacts with the sport through interactive design, social media apps, and powerful streaming capabilities.

Acknowledging the dramatic and fast-paced evolution of recent live streaming technologies, pay TV, and new options for “bundling” programming, Inzerillo stressed that this proliferation of options will “enlarge the pie, as opposed to stealing other people’s slices.” Everyone wins, he suggests: MLB, other companies, and most of all, the consumer — and these options provide robust opportunities for MLBAM to engage and partner with other companies and industries. The MLB’s partnerships and consumer feedback continue to allow customers the ability to be specific about what they want and to choose what they deem valuable. This brings into question how this new technology might advance the “cord cutting” revolution — that is, the rejection of traditional cable service. MLBAM has not only set a trend with their emphasis on cord cutting, but its business model enables content providers to engage in OTT (Over-the-Top) online functions. With OTT and online functions becoming readily available and status quo, these services could lead to a drastic change in bundling and the pay TV model consumers know today.

Source: ballparksonabudget

However, with innovations and customizable content readily available in apps, online, and even in person, one must consider the idea that data can reach a saturation point. The question of oversaturation is worthy of further analysis as technology continues to multiple the means by which we can access mediated content. Inzerillo acknowledged that both as consumers and content providers, we do risk an overload. As a consequence, he says that “we need to make computers work harder for us” with contextual and accurate content — that is, content that provides a framing story for the game, along with useful statistics. By presenting relevant statistics and information, MLBAM strives to make content that is both “elegant and functional”. When considering integrating a new feature or service, Inzerillo says he and his team ask themselves: Is this something that is vital to MLB consumers? Inzerillo was the first to point out that these innovations appeal largely to a younger demographic of baseball fans. In spite of this, the MLB aims to “ride the middle” by enabling additional options of content consumption (both online and in-person) without altering the conditions of the game. Younger generations of fans are looking to consume the game differently, so more information is produced in the form of apps, integrated technology in the ballpark and increased access to statistics. Older generations may not be as accepting of the advancements in technology, which has encouraged MLB to leave the physical game (the player and the baseball itself) unaltered by technology for the time being. Considering the divide between baseball’s traditional and modern fan bases, the question remains as to whether or not these technological advancements increase the risk of overshadowing the game itself. Is the excess of technology in sports truly necessary or has it become cultural pandering?

The possibility of excess aside, these technological advancements do breed positive opinion amongst the modern baseball fan base. While baseball has historically been primarily a “human” sport, it now exists within a specialized environment (the ball field/baseball diamond) that is capable of adapting to the progression of technology — as are the fans themselves. As Inzerillo pointed out during his presentation, there is a vast future in measuring, mediating, and augmenting the ball field to provide a technically rich baseball experience for athletes, coaches, fans of all ages. Player and Ball Tracking via Statcast and PitchFX, pacing the game through high visibility clocks, camera synchronization for instant replay and MLB’s large video infrastructure and network are a few of the technologies the organization has rolled out in the past decade. It’s clear that these impressive developments allow for wider accessibility to the game and the sport in general, as the fan can engage with players and the field in what may translate as a more intimate user experience, or for some fans — particularly those of older generations — a more alienating experience. MLB is both heightening the user experience for the newer generation of baseball fans, while also fracturing the authenticity of the game for the older generations that have less interest in integrating technology into their lives.

A deeper look into baseball’s technology and human elements undoubtedly reveals an interesting relationship between the two and the future advancement of man and machine on the field. In addition to the question of the necessity of technological excess in baseball, another question one might ask is exactly how far can we go with technology on the ball field? Based on the high level of capture technology that MLBAM has access to, the use of multi-camera approach allows an opportunity to document plays on the field in a manner that exceeds the perceptual capabilities of a human on the field. The human umpire is currently the officiator of the game who holds the power of making calls based on his observations. It doesn’t seem out of the question to increase dependence on the camera’s documentation method when making calls and eventually replacing the human officiator with a purely technological device with a lower probability of error. While the camera technology’s documentation can be distorted by technical malfunctions and operator error, there is an element of objective truth in a recorded image that can be viewed and verified by many that that is incomparable to human observation.

When asked about the probability of error with the human umpire, Inzerillo emphasized the high level of training that both umpires and players engage in throughout their careers in major league baseball. He offered MLB’s focus on modern kinesiology, physical training and nutrition as major factors in building more powerful athletes and umpires who have quick reaction time, stamina and clarity of mind. Video coaching is one feedback component that is used with coaches, players and umpires to track habits and analyze opportunities for improvement. MLB considers both their players and umpires to be both physically and mentally elite. They are acutely aware of the need for quick, efficient response, which leads them to continuously focus on improving mind and body of all involved on the field. Video coaching and MLB’s technologies can aid in these training efforts. This marriage of technological and biological optimization ostensibly produced the ideal athlete — one less prone to human error. This kind of bio-technical training and management has implications for other industries, as well. While these developments might lead to increased human potential, they also run the risk of proving exploitative, raising a host of bio-ethical and political-economic concerns. Time will tell whether or not continued advancement and saturation will positively or negatively impact not only baseball, but the way we relate to and communicate with one another in all arenas.

In this cultural landscape largely mediated by digital technology, consumers come across a much wider array of signs, symbols, codes, annotations, etc. With such augmented modes of interaction (such as the previously mentioned apps and interactive field features), this new digital landscape can be considered a form of hyperreality for some consumers. Hyperreality, as Umberto Eco defines it, means the subsumption of the “original” and authentic work to its enhanced, richer “copy”. For our purposes, the mediated MLB experience possibly feels more “real” to the younger generation — those who grew up with satellite, surveillance imagery, and selfies — because they can more closely interact with it. An example of how baseball provides recent generations a more “real experience” by their standards includes the opportunity of making more direct judgment calls while using various viewing tools and apps versus. In “From Work to Text”, semiotician Roland Barthes defines the piece of work as closed, fixed, complete, easily categorized and meant for absent-minded consumption, and the text, in contrast, as open beyond itself, incomplete, intertextual, resisting categorization, and fostering multiple interpretations. With so many modalities through which to engage with the game, and so many layered data streams “enhancing” that game, the live and mediated baseball experience are both power cultural texts that grant audience members tremendous agency in giving them shape.

Even as baseball and other historied pastimes become more and more “mediated,” the sport will indeed continue to be a strong, relevant experience because of its rich history. Among the more fascinating aspects of Joe’s presentation were not only his individual passion for the game but also his emphasis on “trying to tell the narrative of baseball” through technology. It’s not all about using this technology to create flashy boards and analytical data that drive their business; the MLB is interested in furthering the historical narrative of baseball. It’s clear that this game is deeply embedded in American culture. Now that we are moving quickly towards a chiefly digital universe, baseball must also incorporate these elements to stay up to speed and in sync with the modern narrative of our lives. It’s no surprise that baseball has jumped on the technological bandwagon, and the work they are doing at MLBAM is remarkable. However, we must remain critical aware of how this mediation impacts the physical game both positively and negatively,and how technology and people work together in shaping the distinctive time-space experience of our favorite pastime.

Jeanne Liotta An Experimental Filmmaker

Alexis Pittman Humberto Gomez Mohamed Abo el Wafa Samah Abaza

Introduction:

“Each person has the responsibility or opportunity as a human being to discover what their world is made of and what they think about it – to observe and take notes and reflect upon — that’s our jobs as human beings somehow, that’s what I feel like I’m doing when I make things. It’s just my thinking, the real world at last becomes a myth.” -Jeanne Liotta

On March 2, 2015, multimedia filmmaker Jeanne Liotta presented a lecture entitled “The Real World At Last Becomes a Myth: Ruminations on Art and Science.” The title, she explained, was a reference to How the true world became fiction? from the Twilight of the Idols by Friedrich Nietzsche—and in her lecture she examined how media-making shapes our perception of the “real,” empirical world.

This paper is a reflective response to Liotta’s lecture. It explores three main elements:

1. Liotta’s concept of integrating art with science and our perception as “sample audience” to her approach of communicating complex science matter through film. 2. The aesthetics of Liotta’s work and what we got out of it as non-science oriented audience. 3. Liotta’s best work and her awards in the genre of experimental film.

The paper will then conclude with collective insights on some of Liotta’s work as successful examples of experimental films.

The Fusion of Art and Science

When we looked at Liotta’s work prior to the lecture, we weren’t quite sure how to “read” it, or how to understand the means by which it was made. Her lecture, however, provided helpful context regarding her methods, which helped us understand her technique and appreciate the aesthetics of her work. Liotta, who regards her work as a fusion of science and filmmaking, made several references to her love of the stars and the cosmos. Given the widespread fascination with astronomy, we weren’t surprised to find that the audience seemed enamored with this work.

The focus within the majority of her works is on this intersection of art and science. Her most recent body of work, The Science Project, encompasses a constellation of mediums that present an intersection of art, science, and natural philosophy. Her longest project Observando el cielo, from 2007, examines our relationship with space, using seven years’ worth of night-time recordings of the sky. Some viewers, seeing the “natural” imagery in Liotta’s work, might approach it as scientific documentary—and might then be frustrated with her lack of a clear, didactic message. Yet even for those for whom the “message” is unclear, the aesthetic value of the work is apparent: one can’t help but appreciate the beauty of her layered imagery and the nuanced composition of each shot.

Liotta’s Work: Aesthetics & Value

Aesthetics refers to principles governing the nature and appreciation of beauty. Liotta’s appreciation for the aesthetics of science—and her dedication to capturing those aesthetics in her own work, often through several-year-long research and production processes—shone through in her presentation. When we asked her about the challenges of producing such complex imagery, she said: “I believe my job as an artist is to create something that makes people feel more connected to the universe.” Her signature film Observando El Cielo was completed in seven years, Crosswalk took eight years, and her most recent project, Soon, was completed in one year to mention a few.

Liotta experiments even with the “science,” the physics and chemistry, of the image itself—even her own images. For example, “Loretta” was a piece of work she had produced using a “cameraless” process. She explains how she produced a photograph by placing a 35mm negative on top of raw 16 mm stock and then exposed it frame by frame with a flashlight—a process known to experimental filmmakers as a “photogram.” She reminds us that artists will always push their methods beyond what any sophisticated camera can offer—and it’s in this human extension of the machine that we find the most innovative and captivating work.

Another great example we found was Hephaestus of the Air Shaft. Through the course of this film she uses an assortment of shots, all from the same position.

She opens the film with a blank screen and a buzzing noise, then transitions into a wide shot out a window, where a man hanging on a chair in the adjacent building is doing what looks like some metal work. The next shot is a medium shot where you see the metal worker measuring the wall; she then zooms out to reveal the location of the shot. At one point, the focus goes from the metal worker to the welding tool causing the spark, which looks much like a star. Given Liotta’s fascination with stars, one could claim that maybe on some level she was experimenting with different optics and was trying to find celestial events in human labor on earth. The use of light and shadow, framing and composition—including the framing of some shots with household plants, which created a sense of enclosure — along with a mix of grating machinic sounds and ambient music, created a simultaneously mythic and quotidian feel. Such an feeling is only appropriate for our Hephaestus, the “blacksmith of the gods,” in a mundane airshaft—a myth brought down to earth.

She opens the film with a blank screen and a buzzing noise, then transitions into a wide shot out a window, where a man hanging on a chair in the adjacent building is doing what looks like some metal work. The next shot is a medium shot where you see the metal worker measuring the wall; she then zooms out to reveal the location of the shot. At one point, the focus goes from the metal worker to the welding tool causing the spark, which looks much like a star. Given Liotta’s fascination with stars, one could claim that maybe on some level she was experimenting with different optics and was trying to find celestial events in human labor on earth. The use of light and shadow, framing and composition—including the framing of some shots with household plants, which created a sense of enclosure — along with a mix of grating machinic sounds and ambient music, created a simultaneously mythic and quotidian feel. Such an feeling is only appropriate for our Hephaestus, the “blacksmith of the gods,” in a mundane airshaft—a myth brought down to earth.

Liotta’s Best Works:

Over the previous 10 years, science and astronomy have been subjects in most of Liotta’s work. Observando El Cielo, a film that resulted in seven years of recording the cosmos, won the 2008 Tiger Award for Short Films at Rotterdam. It was acknowledged as one of the best in the decade by The Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Another significant piece of work that displayed Liotta’s range as a filmmaker is the critically acclaimed Crosswalk. In this particular work, she stepped out of the realm of science into the spiritual to film a series of Catholic processions that took place on several consecutive Good Fridays. She captured and documented various people for eight years as they took to the streets on the Lower East Side for the Easter celebration. This film adopted a new scientific lens – that of the anthropologist observing the rhythms and traditions of a culture progressing over time.

Liotta’s experimental uses of slide projections, rayograms, and other unique techniques of image creation can vary from one piece to the other. However, her work process seems to have a consistent element throughout—that is, the timeframe she sets or takes to complete her pieces. Her process alone makes her a scientist herself—one who uses film as a medium for her experiments. She observes her world – whether natural occurrences or human behaviors – and she gives each project one a sufficient amount of time, allowing her ideas to develop.

This is Liotta’s process, her “science.” No shot, piece of sound, color choice or transition ever goes to waste, because in the end they all have a purpose and function in communicating their message while producing aesthetically pleasing work. Liotta’s lecture was, for us, an eye opener: it revealed how the medium of experimental film affords a massive range of techniques to simply express a thought or tell a story.

Conclusion:

While, given the scientific subject matter of her work and her experimental process, we might characterize her work itself as a science. On the other hand, Liotta’s work can also be characterized as “abstract art.” Her films can be regarded as abstract audio-visual assemblies that were collected over a long period of time. Even if the “results” of her scientific method are inconclusive, the aesthetic value of her work is undeniable: one can’t help but appreciate the beauty and distinct composition of her imagery, as well as her commitment to such long-term productions.

We leave you with a question Liotta posed in her lecture that is: “What is considered art?” Is it about the process of the artist and the aesthetics of his/her work? Or can it be considered a multidimensional and a subjective field where the work is an invitation for the viewer to connect in one way or the other to the artist’s world?

References:

[1] Smith, S. The enlightenment of Jeanne Liotta. Citizen Science. 02.17.2012.

Retrieved from http://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/2012-02-17/citizen-science/

[2] Land, R.W. (2006). Little Paintings. MFA thesis submitted to the Department of Photography and Film, School of Arts,. Virginia Commonwealth University. P.9

Image retrieved from http://www.jeanneliotta.net/filmpages/loretta.html

Websites:

http://www.jeanneliotta.net/filmpages/loretta.html https://vimeo.com/26745200