Monday, May 4, 2015 at 6:00 pm to 7:45 pm

Jim Paradis, Robert M. Metcalfe Professor of Writing and Comparative Media Studies, MIT; Visiting Researcher, The New School

Abstract: I will offer a broad exploration of some cultural origins of modern surveillance practice as revealed in nineteenth-century urban fiction, journalism, media technologies, and monitorial agencies and institutions.

Laura Di Fabio Henry Vasquez Rokiatou Coulibaly

On May 4, 2015, James Paradis, a Professor of Comparative Media Studies/Writing at MIT, gave a lecture on the cultural origins of modern surveillance practices. Paradis’s lecture focused on how surveillance is a cultural activity, and traces back to the 19th century with evidence of technological advances and surveillance prominent in fiction of the time. This was his first lecture based on a nascent research project.

Paradis began his lecture with a powerful quote from George Simmel, a German sociologist: “The deepest problems of modern life flow from the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society, against the weight of historical heritage, and the external culture and technique of life” (1903). Simmel mirrors three major themes in Paradis’s work:

1. The city as a central locus of modern surveillance,

2. A strong sense of the tension between the individual and the formation of a strong state entity,

3. The identification of this tension in the mental state, drawing on the concept that culture is largely about the mind and the way in which the mind interacts with the materials of the surrounding area (or the body).

Cultural history adds a deeper understanding of the historical questions surrounding the phenomenon of surveillance, and the ways in which surveillance becomes an act that people can actually come to enjoy. Imaginative literature has captured this joy of surveilling by portraying the very real human instinct to observe others without them knowing. The classic examples range from the Watchman on the prowl for criminals doing things when they think no one is looking, to the more perverse Peeping Tom. Cultural history also helps us to understand the relationships between surveillance and media technologies by shedding light on how various technologies have emerged through the pursuit of surveillance to begin with.

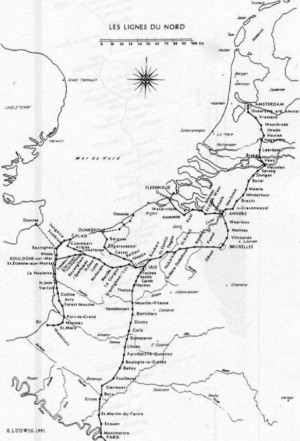

One such great technological development was the optical telegraph, a tool that transmitted messages between two places. Invented by the Chappe Brothers in 1772, the optical telegraph was widely used by the French government during the French Revolution, and quickly developed into a huge network across France. At this time, the notion that a machine could transmit coded messages between places at a rate of 1,380 kilometers per hour (De Decker) – providing a firsthand view of what is going at a location other than where the recipient was at that exact moment – was revolutionary. It was, for all intents and purposes, the original e-mail. With this technological development, the joy of surveillance went even further to include the government. Not only was it a key aspect of war to be able to see your enemy’s position and use it to your advantage, but it also became a governmental tool beyond war to keep an eye on the land.

The optical telegraph also inspired many surveillant narratives in the literary world, particularly The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas: “How wonderful it was that these various signs should be made to cleave the air with such precision as to convey to the distance of three hundred leagues the ideas and wishes of a man sitting at a table at one end of the line to another man similarly placed at the opposite extremity, and all this affected by a simple act of volition.” Dumas captures why, in its cultural reception, the optical telegraph represented a revolutionary development, as well as the potential enjoyment that could be sustained from surveillance. However, it must also be recognized that there are many potential negatives that can ensue from the practice of surveillance, whether it is through governmental surveillance or even interpersonal surveillance.

Paradis made it very clear how important surveillance is for society. Surveillance has become an aspect of our daily lives and has changed the world to make people more informed about current events. Through video recording, cell phone images and other form of surveillance, news media outlets are now able to get information to people in a rapid manner. The distribution of news was a great phenomenon, in the fact that it made news accessible for many people. People were now able to receive news regardless of their location or economic status. Today, current events like the Eric Gardner case receive a great amount of exposure due to the press. The video recording of Gardener’s last moments created a worldwide reaction that lead to the communities protesting, in effort to have their voices heard. Surveillance has made it possible for news media to get information to people through video recording and other media forms.

The Associated Press was one organization that made an effort to share news through different outlets. The Associated Press was aiming to develop news outside of NY and spread it to other places. In 1846, the Associated Press formed when five New York newspapers joined together in an effort to successfully spread news about the Mexican War through Alabama via pony express. The Associated Press encouraged a discovery of and sharing of a wider range of news extending out of the main media hubs, like New York. The spread of the press contributed to surveillance because with more eyes on the world, there were more opportunities to spread news and what was going on all over. If an incident occurred in Connecticut, residents in New York would be aware of this due to the wide spread of news. News was not limited to just the people in that county or community; in fact, it expanded worldwide. Journalists were able to reach out and collect news to spread through surveillance technology.

Paradis mentioned in his lecture the history of authorities, and of the state destroying the press to prevent the spread of ideas. The July Revolution in 1830 is one such example. This revolution was lead by King James X, who ordered the suspension of the liberty of press. Police began to raid the news presses, and angry mobs formed to attack police and protect their voice. People wanted to hear the news and stay informed; they didn’t want things hidden from them. Alexis de Tocqueville imagined a public being able to monitor the government. Tocqueville believed that Americans were able to set aside some of their selfish desires, people would be able to make a self-conscious and active political and civil society. Tocqueville believed that the state should not keep people ignorant, and they should be entitled to be informed. The idea of civilians holding the majority of the power is something that can be deemed impossible to our society; because without the rule of government or higher powers there would be no order set in place. Instead his belief formed danger, because people would be able to live without any type of control. Tocqueville thought that surveillance and the spread of information would give people the power over the government, and that power can be used for good. However, a society where people hold power without any control can be detrimental because people can be just as abusive of power as government can. Nevertheless, people should have a right to be informed of occurring events because we need to know what is going on in the society that we live in.

Nowadays some type of news surrounds many people in our society. Social media has become a big surveillance source in delivering the news instantly. People in the society can share or post information on events occurring or events they personally witnessed. Social media is a big outlet of news; many people simply sign into their Twitter of Facebook accounts to receive news before turning on the television.

Paradis touches on police, visualizing the city, and feuilliton. 1829 brought the Metropolitan Police Act in London, then in 1845, the Municipal Police Act; New York’s Metropolitan Police Act went into effect in 1857. The police were another seemingly ubiquitous surveillant force. The police act was essentially a social protection to society in the mid 1800’s. Though several police acts were passed; it was an uncertain idea to the community because people didn’t think they would be needed or for what they’ll be needed for. Police also did not want to wear uniform and The New York Times thought is a good idea for police to be wearing uniforms other wise how will we find them. If we fast forward to our modern time today; there are uniforms for almost everything and it real easy to identify a person according to the uniform they wear.

In On Duty with Inspector Field by Charles Dickens says “Inspector Field’s eye is the roving eye that searches every corner of the cellar as he talks. Inspector Field’s hand is the well-known hand that has collared half the people here, hand motioned their brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, male and female friends to New South Wales. Yet Inspector Field stands in this den, the Sultan of the place. All watch him, all answer when addressed, all laugh at his jokes, all seek to propitiate him.”

On Duty With Inspector Field / Charles Dickens

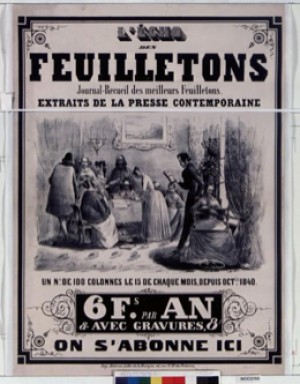

Later on, daguerreotype images were used to illustrate non-fiction accounts of the city based on extensive surveillance of the public. Photographs later offered nearly-instantaneous and easily replicable representations of everyday urban life. Feuillitons, newspaper supplements that combined fictional detective stories and news, allowed another means of observing urban life; we might draw a comparison to today’s celebrity news and reality shows. Ned Buntline’s 1848 The Mysteries and Miseries of New York offered to lay before its reader “all the vice of the city, to lay open its festering sores, so that you and the good and philanthropic may see where to apply the healing balm.” Their often sensational depictions of criminality, some suggest, served as a means of differentiating obedient urban subjects from criminals.

Nowadays, we equate surveillance with closed-circuit cameras, drones, and massive databases of personal information. Police exploit their access to these technologies to monitor suspicious behavior and identify suspects – activities that could be justified as “fighting crime” – but such surveillance and data mining also represents an invasion of privacy. Fingerprints are still used to identify individuals, but a quicker means of identification is with the new technologies of facial photo scanning. Authorities also use social media to monitor conversations and posts and flag suspicious online activity. We might wonder if surveillance will grow to point where authorities can find anyone, anywhere, at anytime.