Andrew Uroskie – Group 1

Gabriel Clermont

Andrea Crowley-Hughes

Alexandra Garza

Wei Lee

Devin Dowling

Site Specificity in the Digital Age

Immersive installations that combine music, visual art, and video are not out of the ordinary in today’s gallery scene, but in the mid to late 1960s, such installations were part of the forward-thinking movement known as “expanded cinema.” Andrew Uroskie, Associate Professor of Modern Art History and Criticism at SUNY Stonybrook, explored “Selma Last Year,” a 1966 collaboration between “happenings” artist Ken Dewey, civil rights photographer Bruce Davidson and minimalist composer Terry Riley, in an Understanding Media Studies lecture on November 10, 2014.

In addition to Riley’s compositions, “Selma Last Year” featured “audio portraits,” or recordings from Dewey’s interviews of participants in the civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Recorded with a unidirectional microphone, the audio portraits capture the voices and opinions of protesters and citizens as well as the audible chaos of the marches. According to Uroskie, Dewey asked open-ended questions that were “intentionally blank” as opposed to leading questions. Unlike biased captions in press coverage of the marches, the quotes provide a nuanced picture of people’s reactions to the protests, a framework which is complemented by Davidson’s photographs. While other documentary photographers of the time rode on pallets and focused on leaders, Davidson marched as he photographed, and captured portraits of individual marchers rather than crowds.

After being presented to a racially mixed Unitarian Universalist congregation in Chicago, the exhibition went to Lincoln Center as part of the 1966 New York Film Festival. Dewey shifted his presentation strategy to evoke more of an emotional response from the New York audience, which was more likely to consist of white, affluent museum goers. Davidson’s images were placed closer to the ground on low-lying plinths, functioning to make the viewers conscious of the images as tomblike structures. A “palpable awkwardness” was intentionally created by requiring viewers to actively alter their position to view the images. A separate downstairs space gave the spectator the feeling that, as in the marches themselves, “you had to go down to be involved.” A television screen, through which viewers could see video of themselves looking at the images, was also added as a way to disorient the spectators and see themselves from the outside. Because the audio was looped and there was a delay purposefully built into the sound design, the juxtaposition of sound and image changed continuously throughout the exhibition. A disjunctive experience was established, which spoke to the social inequality that remained after the march a year before.

The idea of site-specificity is central to Uroskie’s lecture. Although the term itself is much more recent, the notion of site-specificity is crucial throughout art history. As Uroskie stresses, audience engagement can define a work’s relevance and meaning. Site-specific art gained steam in tandem with the great social revolutions of the 1960s. Prominent artist Richard Serra, known for his minimalist yet grand scale sculpture and subsequent blockbuster exhibitions, famously said, “to remove the work is to destroy the work” at a 1985 public hearing.

Yet the impact of site-specific art, no matter the medium, depends not only (as its name implies) on the site; it alsorelies heavily on the participant. Identities are formed and reshaped as a result of the entire process and incorporation of all five senses. However, this theory sparks an intriguing dialectic that Uroskie tapped into during his lecture. If a particular work’s setting is so important, but so is its audience, how would an artist or its viewers go about sharing it? With pieces like “Selma Last Year” and other works that are intended to spark social change and unveil truths, how does one go about making site-specific art accessible? What is lost when art is transported, literally or figuratively?

For an audience of New School students engaged in careers and lifestyles in which social media is an everyday reality, it was natural that several audience members related the participatory nature of “Selma Last Year” to the very transportable media we view on our phones and computers. Reading the transcript slides of Dewey’s “audio portraits” on Selma in the presentation felt much like following a Twitter hashtag in response to a social justice issue. In each case, viewers see conflicting opinions in the same digital “site,” one that is continuously changing as users introduce new content onto the feed. Examples of recent hashtag dialogues engaging issues of racial equality in society and pop culture include #solidarityisforwhitewomen, #notyoursidekick and #iftheygunnedmedown. Although some discordant dialogues can exist in these continuing discussions, social media users tend to filter the seemingly limitless amount of information on the Internet based on their beliefs and comfort levels. New personalized technology by Google and Facebook can automatically impose filter bubbles on a search for information, tailoring the results to the user’s past search history, location and other information.[i] It remains an open question whether interactive media projects can be developed to subvert these filter bubbles and create the self-reflection “Selma Last Year” engendered. Since multimedia installations like Dewey’s would be seen as “normal” today, and issues of privilege can easily allow social media users to filter out discomforting discussions, perhaps a new approach is needed.

The new film Selma centers on Martin Luther King Jr. and others during the Selma Marches. Written by Paul Webb and directed by Ava Duvernay, the film is scheduled to be released in theaters on December 25, 2014, in New York.[ii] Selma was screened at the AFI Festival this month, generating positive feedback and talks of potential Oscar wins.[iii] “Selma Last Year” was displayed a year after the actual event to audiences who experienced the event either directly or indirectly, but this film is screened decades after the event took place. The question is this: Why make this film now for an audience that has largely not experienced the Selma Marches?

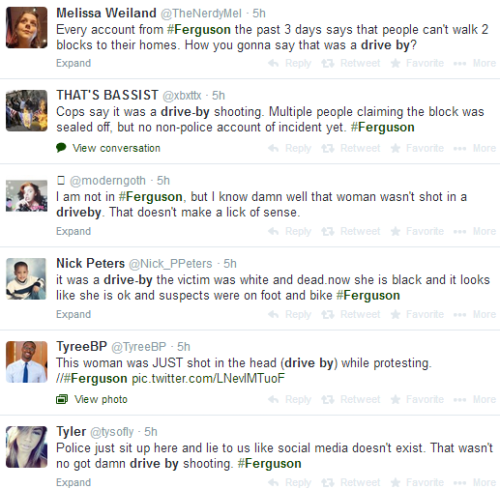

Here’s one reason: While the Selma Marches may have occurred over 45 years ago, the racial tensions that fueled the event are still prevalent today. In the United States there has been a string of unarmed black men being shot and killed. Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown are cases that sparked nationwide interest, but there are many more in addition to them. In August 2014 alone Eric Garner, John Crawford, Ezell Ford, and Dante Parkers — all unarmed black men — were killed by police.[iv] The officers responsible for murdering those they are supposed to serve and protect are rarely held accountable for their actions. Protests are currently being held in Ferguson, Missouri, but authorities in Ferguson have been blocking mainstream media outlets from covering these events.[v] If it were not for social media, particularly Twitter, this information may have never come to light. Residents of Ferguson, civilian protesters, and media personnel use the hashtag #Ferguson on Twitter to give updates on their current situation. Using their smartphones, they can instantly record and post online videos of police brutality toward the peaceful protesters. The format of social media allows news to be disseminated to the masses immediately by unofficial sources. This raises more awareness than a mere exhibition could.

Revisiting the past through watching Selma is important for understanding the present. Seeing similarities of the struggle in the Selma Marches reflected in the present struggle at Ferguson can motivate audiences to seek out justice and equality for all. Uroskie states that in order to garner such a proactive response from an audience one must send messages that subvert the dominant communication networks. Is a film enough to incite the American people? On its own, perhaps not. However, the current landscape of communication is one of mixed media platforms. In conjunction with Twitter and other social media, a film very well may incite action or a change of perspective from the public. If the same topic persists through numerous forms of media, that topic is more likely to become a genuine concern in people’s minds, and then actions for change can take place.

Online documentaries, in many ways structurally similar to ‘expanded cinema’ of the ’60s and ’70s, are beginning to gain prominence. While expanded cinema projects utilize their physical spaces as part of the art, digital transmedia projects are able to create their own literal and figurative “sites” in which the content is viewed. Much like how artists in the ’70s confronted and often rejected the established paradigm of audiences sitting in large theaters en masse experiencing a film, recent digital projects that go beyond just having a web component supporting a theatrical release have created spaces within which the entire work is able to be experienced. Institutions like the Tribeca Film Institute’s New Media Fund (in existence for the past four years), have worked to support and promote “non-fiction, social issue media projects which go beyond traditional screens – integrating film with content across media platforms, from video games and mobile apps to social networks and interactive websites.”[vi] The most prominent recent example is Elaine McMillion’s Hollow, which utilizes “documentary portraits, interactive data and user-generated content to support engagement and inspire”[vii] all accessible through one website.

“Hollow” has received acclaim from a wide range of mainstream platforms, including The New York Times, Huffington Post, and PBS, and was the winner of a 2013 Peabody Award. While the content is engaging and well produced, what “Hollow,” and the other TFI New Media awardees don’t contain is the symbiosis between interactivity and cross media content that “Selma Last Year” achieved. While meticulously crafted web and video content are on display, audiences are unable to participate in truly additive ways. “Hollow” would still exist without an audience. At the same time, social media campaigns effectively utilize the voices of the participants to enhance the art, but they rarely contain a rich media experience. “Selma Last Year” was both reflective and directed. It fully commented both on the experiences of the people engaged in the march, and also on the audience’s reactions to the exhibit itself. It will be interesting to see if projects in the future don’t just amplify the voices of their subjects, but also reflect back the ideas of their audience.

Uroskie mentioned that some of the most interesting work is being done at the intersection of art and digital communication networks, and perhaps as activists explore this area they can develop methods to evoke lasting emotional responses to the inequality that persists today. Canadian artist Janet Cardiff’s recent installation at the Banhoff train station addresses the constant “overlay” of information that makes us constant spectators. The artist gave viewers iPods with cameras and headphones through which they could juxtapose pre-recorded narration and images in the station with the real-time environment. In the past, artists had to only consider the physical location of their work and how to incorporate the space into their art to fully engage the viewer. Now portable technology and social media platforms need to be considered when constructing works because they allow viewers to contribute content. This format, in which the handheld device is part of the experience rather than a site into which viewers can “escape,” holds promise for fostering true engagement around issues of privilege in the digital age.

[i] “Filter bubble.” Wikipedia. 19 Nov 2014 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filter_bubble> See also Pariser, Eli. The filter bubble: How the new personalized Web is changing what we read and how we think. Penguin, 2011.

[ii] Farber, Stephen. “‘Selma’: AFI Fest Review.” The Hollywood Reporter. 11 Nov 2014. 16 Nov 2014. <http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/selma-afi-fest-review-748467>

[iii] Dupont, Veronique. “Oscar Buzz Swirling around MLK film ‘Selma.” YahooNews.com. 14 Nov 2014. 16 Nov 2014. <http://news.yahoo.com/oscar-buzz-swirls-around-mlk-film-selma-013844728.html>

[iv] Harkinson, Josh. “4 Unarmed Black Men Have Been Killed By Police in the Last Month.” MotherJones.com. 13 Aug 2014. 16 Nov 2014. <http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/08/3-unarmed-black-african-american-men-killed-police>

[v] Zara, Christopher. “Ferguson Media Blackout: Mike Brown Shooter Hidden, Journalists Arrested, Secrecy Backfires.” International Business Times. 14 Aug 2014. 16 Nov 2014. <http://www.ibtimes.com/ferguson-media-blackout-mike-brown-shooter-hidden-journalists-arrested-secrecy-backfires-1658836>

[vi] “About the TFI New Media Fund.” Tribeca Film Institute. 24 Nov 2014 <https://tribecafilminstitute.org/pages/new_media_about>

[vii]“Hollow.” Tribeca Film Institute. 24 Nov 2014 <https://tribecafilminstitute.org/films/detail/hollow/artist_programs/tfi_new_media_fund/_/_/>

- Mary Flanagan – Changing the World Through Values at Play - September 15, 2014

- Caitlin Burns – Lessons from the Story Business - October 6, 2014

- Mary Flanagan – Group 1 - October 7, 2014