Wareham Williams – Group 2

Shannon Smith

Tanya Somasundaram

Sarah Cerio-Stokes

Peace Is Not “Kumbaya, My Lord”

In today’s society the phrase “world peace” is often associated with individuals who do not have a clear understanding of the complexity it holds. Frequently, this phrase is used as an advertisement to gain support. For instance, a woman competing in a beauty pageant will use the phrase as a generic answer in the hope of gaining votes. However, when the notion of “world peace” is referenced by Jody Williams and Mary Wareham, it has nothing to do with the idea of utopia; as Williams said during her famous TED talk, peace is not “Kumbaya, my Lord.” Instead, it has everything to do with actions of hard work and commitment. On October 20, 2014, in an Understanding Media Studies lecture, Williams and Wareham spoke about their tireless efforts to spread peace throughout the world.

Wareham and Williams act and speak on behalf of a global coalition that aims to encourage debate over the ethics of automated weapons. Both of these women are highly educated, outspoken, and brave. Williams is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Instead of continuing to provide adjectives that emphasize how great these women are, however, we have decided to describe them in regards to the role they play in our society. First, we choose to emphasize their role as activists. Now, doesn’t it sound like we have diminished their greatness when we used the word “activists”? As we know so well, word choice matters. Conveying a message and/or meta-message effectively is determined by the words and images we choose to frame those messages. So yes, this article will be framed around issues such as: semantics, branding, and the role of media in this noble fight for world peace. We’ll also integrate a discussion of gender issues, which inform all of these communication choices.

Wareham and Williams act and speak on behalf of a global coalition that aims to encourage debate over the ethics of automated weapons. Both of these women are highly educated, outspoken, and brave. Williams is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Instead of continuing to provide adjectives that emphasize how great these women are, however, we have decided to describe them in regards to the role they play in our society. First, we choose to emphasize their role as activists. Now, doesn’t it sound like we have diminished their greatness when we used the word “activists”? As we know so well, word choice matters. Conveying a message and/or meta-message effectively is determined by the words and images we choose to frame those messages. So yes, this article will be framed around issues such as: semantics, branding, and the role of media in this noble fight for world peace. We’ll also integrate a discussion of gender issues, which inform all of these communication choices.

Semantics Behind Killer Robots or Why Branding Your Ideas Is Important

Before jumping into the notion of branding, let us give you a little background information. According to Wareham and Williams, within the next 20-30 years – maybe sooner – the responsibilities of a soldier will be passed down to a machine. The primary quandary, then, is that society will be relying on a machine to make vital decisions about ending human life. Ultimately, a machine will have to discern between someone who looks suspicious (i.e. a terrorist) and a “normal” civilian. Perhaps a machine will mistakenly kill an innocent civilian due to technological complications. A new conflict arises: who will be held responsible for the death of an innocent civilian?

Posing this question to ourselves, we started thinking of Heidegger’s “Questions concerning technology”, especially the point where he references an old problem in philosophy: the question of causality. Briefly, when one creates things, one begins the creation process with the causa finalis on mind. This includes: the final outcome of the creation, its looks, and purpose. A chair cannot be created if the inventor did not imagine a purpose for it (we need something to sit on) or what it will look like (which informs what materials are needed and who will sit on it). In the realm of weaponry, if someone creates a firearm or bomb, he/ she is certainly not creating it for the purpose of flowering a garden. The purpose of a gun is to hurt or kill someone. The same is true of a machine to be used in warfare. Isn’t, then, creating such a weapon similar to or even the same as premeditated murder? These killing machines are an extension of everyone who sent them out to kill.

There’s no concrete answer to the question of accountability. Thankfully, the Campaign to “Stop Killer Robots” is meant to end the development and usage of these machines before the question of responsibility will require an answer.

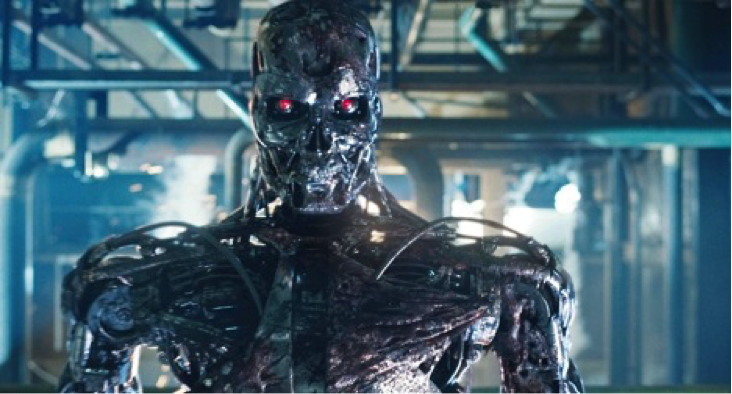

When we hear the term “Killer Robots” our minds typically conjure up images of Terminators and Jaegers from Pacific Rim. Yet the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots uses the phrase to refer to all lethal autonomous robots — including landmines (which could be called the stupid robots) and drones (the smart killer robots). The campaign recognizes that the phrase “killer robots,” while sensational, certainly draws attention.

Nice Q’s from audience “Do references to science fiction by the media help or hurt the campaign” Our answer? We want to catch your attention

— Stop Killer Robots (@BanKillerRobots) October 20, 2014

The words were chosen carefully as a branding strategy to attract people and inspire them to learn more. If, instead, they chose this name: The Campaign To Stop Fully Autonomous Weapons – would “ordinary” people understand it, and would they pay attention? These choices are partly due to the novelty of the issue in the media — they need to create a recognizable visual identity — and the excitement surrounding it. The media are still adjusting and learning about the issue as well.

After carefully wrapping their mission around the notion of killer robots, the campaign had to choose the visuals and colors to complement the idea and to work in liaison with words. Brands are embodied in shapes and colors; and those elemental forms are often the most immediate and direct way for entities to convey their identities to a target audience. Colors and shapes work in harmony with each other. The CSKR campaign has chosen strong colors, black and red, to convey the message of blood and death caused by killer machines, while the chosen shape is that of a simple crosshair. These branding decisions speak of an effort to both convey gravity, while steering away from the Sci-Fi hype that surrounds “robots” in people’s minds.

“We couldn’t find any suitable women”

In addition to their initiatives to ban landmines and killer robots, Wareham and Williams briefly tackled the subject of gender issues in humanitarian disarmament. In May 2014, governments from around the world gathered in Geneva to debate whether lethal autonomous weapons systems should be legal. Eighteen experts were asked to present their views on the technological, ethical, legal, operational, and military aspects of “killer robots.” None of these experts were female. According to Williams, when the blatant lack of gender diversity was brought up, the U.N. contended that, despite women making up half of the world’s population, they “could not find any suitable women” for the panel. The exclusion of women from dialogues on disarmament and arms control is not just offensive; it is dangerous. Williams stressed the importance of women’s involvement in discussions pertaining to weapons and security issues. She argued that the exclusion of women from these conversations suggests that women are not taken seriously in matters of security. Ultimately, without a woman’s perspective on security, weapons, and disarmament, Williams believes that nothing will change.

Citing the UN Security Counsel’s Resolution 1325, which commits to the inclusion of women in discussions of peace and security, Williams argued that “[writing] words on paper…did not translate to anything meaningful on the ground.” To combat this, the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots’ has sent letters of protest to all all-male panels tackling the subject of disarmament. As Williams points out, “agreeing [about the need for female representation] is irrelevant if you don’t use the power that you have to change the situation.”

How To Make Something Extraordinary Happen

Williams and Wareham leave us with several guidelines for crafting a politically sensitive message to reach a global audience: Remember to think strategically, both within an organization and individually. Be proactive; use determination, courage, and lots of imagination as your weapons. Whether working to try to solve a social justice issue or on the commercial side, we all have to find ways to navigate in a sensationalistic culture to get stakeholders to take our concerns and goals seriously. We might have an idea about how things are supposed to develop with our issue, but the public, or the media, certainly has other ideas. This is when strategy comes into the picture, serving as a beacon, a reminder of our goal.

When media started sensationalizing their work, Wareham and Williams did something smart: instead of running away from it, they responded by adopting the term “killer robots”, which turned out to be a good way to begin the dialogue with both media representatives and the public. Jody Williams won a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to eradicate landmines, working as the chief strategist of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines. Now she has teamed up with other female peace laureates to empower women to fight violence, injustice and inequality. Thus, not only are these women fighting against killer robots; they’re also fighting for women’s voices to be heard among global debates on security, an issue that’s certainly blind to race, class, and gender.

- Mary Flanagan – Changing the World Through Values at Play - September 15, 2014

- Caitlin Burns – Lessons from the Story Business - October 6, 2014

- Mary Flanagan – Group 1 - October 7, 2014