Chi-hui Yang – Group 1

Lindsey Clark

Anitra Lourie

Zoe Middleton

Curating At The Crossroads

1. Why A Manifesto?

We’ve chosen the format of a manifesto to respond to Chi-Hui Yang’s talk for two key reasons. Curation and “high art” are often seen as inaccessible topics, and we hope that the energetic and mass-audience tone of a manifesto will help to make the subject matter more approachable. Secondly, our response to Yang’s lecture includes several re-imaginings of curatorial practice and provides loose guidelines for each. Since manifestos frequently carry both radical visions and concrete action steps, the format felt exceptionally appropriate.

2. Visual Elements

Interspersed through this work you will find graphic and visual elements meant to help convey some of our concepts. These visuals will hopefully allow for a richer understanding of our arguments and permit readers to interact with theoretical and experimental proposals on a more concrete level.

3. The Importance of Questioning

Before providing any speculative advice on how to curate, we must address the question of, well, questioning. Questioning and knowledge seeking is the bedrock of knowledge production (and a good curator is a knowledge creator par excellence).

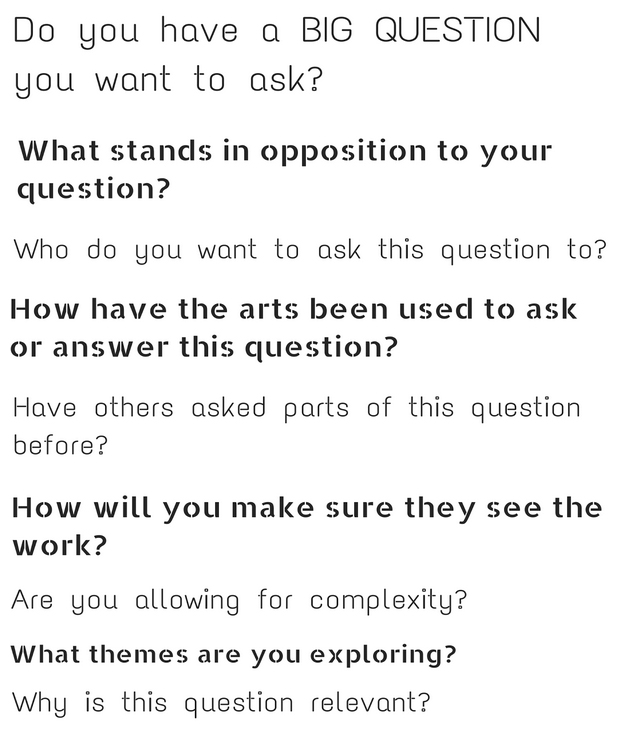

Below we’ve provided a visual that poses some important questions to consider when approaching curation.

Types Of Curating

Categorized Curating

Chi-hui Yang challenges some of the standard forms of curation that often categorize artwork. He explains that these “safe” forms of curation do not always generate new perspectives and methods of engagement. The ever-popular retrospective format that focuses on one artist, time period, or location, can offer a somewhat limited view of the inspirations, conflicts, and influences of the work. The upcoming retrospective of Taiwanese artist Tsai Ming-liang at The Museum of the Moving Picture is an example of this style of curation. While certainly providing an effective introduction to the filmmaker, the choice to categorize the artist’s work as strictly Taiwanese is problematic. Ming-liang’s work, Yang points out, is frequently cosmopolitan, often French-financed and made for European audiences. Interacting on a broader, if more ambiguous, level with the work could yield much more compelling conversations and benefit the audience.

Radical Juxtaposition

Radical juxtaposition is a curatorial strategy that invites complexity instead of balking at it. The goal is to present a challenging combination of works that can produce new questions and perspectives in communal contexts.

Yang admits that this strategy can be hard to swallow for some audiences, but maintains that adventurousness, like curiosity, is a crucial part of creating new knowledge. Consider, for example, the recent combination of Stanley Nelson’s film “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution” and Kevin Jerome Everson’s “ Park Lanes” in The Museum of Modern Art’s Documentary Fortnight. The two films have completely different narratives, styles, settings, and distribution, yet their pairing might bring the viewers to make new and unique connections. These reflections offer an alternative way for the viewers to engage in the public conversation about race, labor and social movements.

What follows are speculative forms of curation that we’ve developed in response to Yang’s lecture. These are by no means edicts for curatorial practice, but rather experimental guidelines.

These probes are meant to help viewers grapple with the complexity of some subjects and to reduce the distance between art and audience.

The Complicated Biography

The Complicated Biography is a riff on the more sanitized retrospective. In this strategy a curated show must deal with the complex or problematic elements in the artist’s past, process, or common interpretations of the artist’s work.

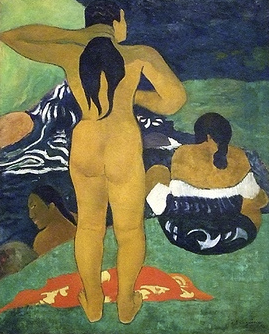

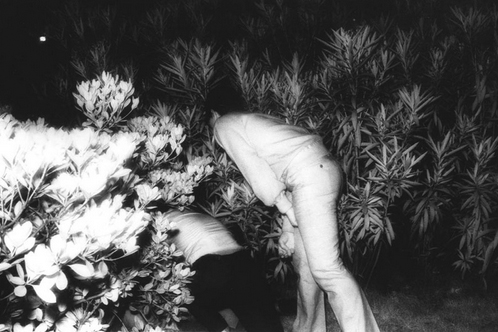

For example, new medical speculations as to the physical and mental state of Vincent Van Gogh (as well as the standards of treatment at the time) could help to frame his work just as interestingly as the personal letters that are frequently used to provide context for his paintings. Similarly, Paul Gauguin’s work could be presented as an example of the male gaze, part of Orientalist narratives of the South Pacific, or presented in (radical) juxtaposition to the Japanese photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki’s voyeuristic, appropriative series that captured public displays of sensuality in Tokyo’s parks almost a century after Gauguin’s death.

Gaugin’s Bathing

Kohei Yoshiyuki’s The Park Series

Community-oriented Curating

We’ve created the term community-oriented curating to reference curatorial strategies that not only ask difficult questions, but also design their shows with the needs of various communities (especially otherwise disenfranchised groups) in mind. Those needs should be reflected in a variety of ways — from from the themes chosen to the accessibility of the exhibition space.

If one imagines a spectrum with art at one end and audience the other, there are numerous social, environmental, and cultural barriers that prevent audiences from experiencing a show. Some of these barriers are illustrated in the diagram below. A community-oriented curator must consider such concerns in mounting and promoting their show.

Embedded Curating

Embedded curating is a term we’ve developed to discuss exhibitions that are community-oriented in their approach, but also located within the physical communities where the art was created or those where the themes of the show are especially salient. An embedded show is deeply reflexive to social issues and interests of the local population.

The Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance is a gallery-education space that caters to the communities of Washington Heights and Inwood. Their current exhibit, Women in the Heights: The Human Essence, “featur[es] works by women artists of Northern Manhattan, tackling issues affecting humanity”. Although their practice closely mirrors what we’ve described above as “embedded curating” the hours of the space are prohibitive for some community members.

Mobile-adapted Curating (The Tech Solutionist Approach)

So many present-day interactions with art and film happen outside of galleries, cinemas, and museum spaces. While experiencing works in those contexts is certainly valuable, it is also extremely formal. Mobile-adapted curating allows visitors the chance to engage with art in more intimate, comfortable settings by creating content that can be consumed on tablets, smartphones and the like. This style of curating, which is already being explored through various art blogs, websites, and online magazines, offers a flexible and contemporary platform for creative expression. Additionally, in an increasingly mobile world, this method once again increases accessibility and allows the audience to pause and return to works for multiple viewings and reference work from any location.

Small-Scale Curating

Small-scale curating is exactly what it sounds like. Instead of mounting large shows, an ambitious small-scale curator would select a handful of works to be shown to a smaller audience in a meditative space. This approach allows for curators to ask very concise questions of a work and for visitors to “lose themselves” in a piece more easily than they would in a crowded museum hall. Small-scale curating acts in opposition to the multi-tasking impulses of the day and brings the intimacy of mobile-adapted curating to traditional art spaces.

(Left) The Louvre gallery that houses Mona Lisa is notoriously crowded.

(Right) Houston’s Rothko Chapel is a permanent display from a private collection, but an excellent demonstration of creating a contemplative space for audiences.

Conclusion

With the increased variety of mediums and settings within the profession, curation is at a crossroads. Contemporary curators have the opportunity to address major social issues across diverse platforms and for an equally diverse audience. Curators such as Chi-hui Yang endeavour to challenge the existing patterns of art viewing and utilise his projects for social discussion and exploration. We challenge the contemporary curator to step outside the box and consider some alternative methods of art organizing. Acknowledging the diverse factors that inform art making and prioritizing viewer experience can help stimulate conversations on specific timely and critical topics and promote the civic engagement needed for a radical form of change.

- Garnet Hertz – Critical Making: Foundations and Processes of Critically Engaged Design Practice - February 9, 2015

- Ben Vershbow – Time Machines, Community Gardens, and Other Metaphors for Libraries

Dragan Espenschied – Understanding the Creation of Artifacts of Digital Culture - February 23, 2015 - Jeanne Liotta – The Real World at Last Becomes a Myth: Ruminations on Art and Science - March 2, 2015